We are happy to report that our entire audiovisual (AV) collection is processed! We have nine boxes of AV materials, including audio reels, cassettes, records, 16mm films, floppy disks, VHS tapes, CDs, wire recordings, and microfilm.

Here’s a breakdown of how we process AV material:

- We find AV items mixed in with the regular collection, or acquire larger items (such as the 16mm film reels) in their own containers that are usually not preservation-friendly.

- We remove the AV item and place one copy of a transfer form in its original location, and keep the other copy with the item. This way, we can note the intellectual location of the item, even though it will not physically be housed in its correct subgroup and series.

- We try to deduce the content of the AV item, and make some decisions regarding the importance of keeping and also digitizing the item. Some items are labeled (though labels aren’t always correct) and some are not. Based on labeling and original location in the collection, if an item seems important — such as Board minutes — we listen to it or view it and, if necessary, create a digital version. Some items may not have content on them at all (blank cassettes, for example), or may have degraded so much that they are unable to be viewed or listened to. These items are weeded from the collection.

- In order to be efficient and cost effective when digitizing, we group materials by format and determine the best vendor for the process. We are lucky enough to have much equipment to play and digitize various media here at the Center for Jewish History, including cassette players, record players, disk drives, etc, though we did (and many other repositories do) send out certain formats for digitization. For our films and audio reels, we used MediaPreserve. Once a digital file has been created, we ingest the file into our digital asset management system and gather metadata about the digital version. This digital file has now become its own item in our collection, and is publicly available through the Center for Jewish History’s Digital Collections.

- When the digitization process is complete, we carefully rehouse the AV item with its transfer form, usually with materials of the same format, in preservation friendly containers. Some materials (like cassettes and diskettes) can be stored together, while other materials (like 16mm film) are prone to decay and should be housed individually. We also try to keep digitized items in separate boxes for easier retrieval.

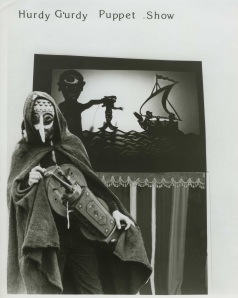

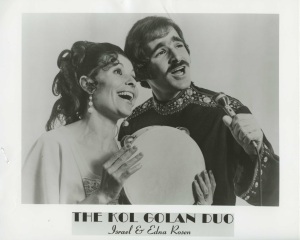

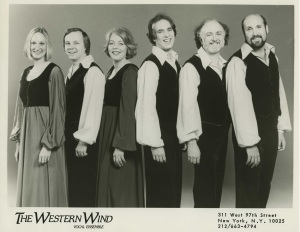

- We then create a separate AV folder list to keep track of the AV boxes and their contents and location, and connect all digital versions to their physical counterparts through links in our regular folder lists. In addition to our digitized films, below are some links to other digitized AV items of interest in the collection, and in case you forgot what some of these old AV formats look like, at the very bottom are photographs!

FJP Executive Committee Special Meeting on Merger, 1985

UJA Campaign Radio Spots, 1974

UJA Council of Organizations Yiddish Radio Programs, 1976

UJF Taskforce on the Jewish Woman: Conference on Women and Leadership, 1987